When the TV cameras are turned off

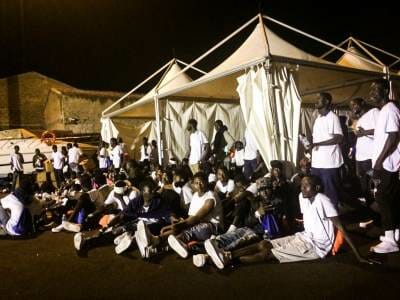

On August 24, the Italian ship Vega carried 548 people who had been rescued at sea to Palermo. The majority of those aboard were women and children. Amongst them were many unaccompanied minors; 130 on arrival. Yet after the identification procedure had been carried out, that number somehow had gone down to 45.

The reception centres for minors are overflowing, nonetheless places were found for all. Many shadows can be cast over how this was achieved, taking into consideration that only that very morning the Prefect of Palermo declared in front of the press that there was a lack of available places to house minors. Yet the same afternoon, the council magically found a place for everyone. The fear is that many migrants magically became adults, especially as the initial identification of those who arrived on the previous boat also appeared very unclear.

Unfortunately, even those who are correctly recognized and processed as minors, still risk getting lost in the system. They may venture from their allocated accommodation in order to reach other parts of Europe or reach other people from their own countries in other cities; or worse still, end up in prostitution rings, which begin with Palermo’s own Parco della Favorita. Distancing themselves from designated centres poses a further problem for minors too: the loss of access to the professional services in place within centres for unaccompanied minors.

For the CAS* in Piano degli Albanesi, Partinico, Marsala, Castelvetrano and even in some of the SPRAR*, there is only one request being raised by the asylum seekers: to be able to have the necessary documents required for them to reach their desired destination. The question Is everything ok in there? is often ignored by those who have been staying there for over 12 months and whose lives consist only of eating and sleeping. The lucky ones may have the possibility to follow a few Italian lessons. But they are asking to work, “I don’t care what I do,” says one of the residents in Piano degli Albanesi, “I’ll even clean toilets. Just let me work. I have a family back home who needs me. For the moment I’m sending them part of my pocket money.”

They ask for help in order to speed up the process of issuing the necessary documents for them to leave the centres. They no longer have the energy to stay still. Many of them do not realise, however, that when they leave the centre, it will not be easy to find work or a place to stay. There is a lack of adequate support for social integration on the part of both the government and those running the centres, for whom migrants are just numbers. Last week a resident of the centre at Piano degli Albanesi gave us the happy news that his request had been approved. Despite his contentment, uncertainty was written all over his face when we asked him What are you going to do when you leave here? He then turned it round, asking us What am I going to do when I leave here?. He has spent over a year in a town where he does not know the language and then it leaves him to fend for himself after it has earned money from him.

We are good at showing how welcoming we are in front of the television cameras. When the boats arrive, we give the best of ourselves, because the world is watching us. But when the lights go out, all the good intentions disappear – just as if they were the buses that carry the hundreds of men, women and children from the port of Palermo to other Italian cities – taking them away, leaving behind just a grey cloud of exhaust.

Giovanna Fioravanti

Borderline Sicilia Onlus

*CAS – Centri d’Accoglienza Staordinaria: centres for extraordinary reception

**SPRAR – Sistema di protezione per rifugiati e richiedenti asilo: protection facilities for asylum seekers and refugees

Translation: Claire Owen