We have lost even the last speck of humanity

The accounts provided by doctors present at the latest disembarkings at Palermo, Trapani and Agrigento leave no doubts about the atrocious situation being experienced by thousands of long-suffering people now arriving in Europe.

More than five thousand people arrived last weekend, mainly from Eritrea, Nigeria, Ghana and Afghanistan: all of them fleeing situations of war, misery and abandonment, situations which share Libya’s future of injustice, violence, theft, torture and death.

Death is always waiting in such situations, and yesterday a women died before she could be rescued by the Coast Guard ship CORSI. She died before the eyes of her husband and sister, both of whom must now continue to live their lives with this endless pain, a pain made still worse in the knowledge, as we learned from the husband, that the woman was pregnant. Thus, as of yesterday, Europe is once again tainted by two more appalling crimes, a murder which passes under silence, which no photographer could has immortalised – and with everyone’s tacit blessing.

The woman’s husband and sister have been transferred, along with another 370 migrants, to the sorting centre in Siculiana (villa Sikania). The centre, designed for just over 200 people, is thus now beyond capacity. Within 48 hours they will then be moved North, if the prefecture can locate the coaches to make the transferals.

The migrants saved by the Médecins Sans Frontières ship ‘Dignity I’ were disembarked at Trapani: 380 women, men and unaccompanied minors. Here too 15 people were immediately taken to hospital: a sign of the difficulties which are always present during these journeys. Everyone was put onto coaches bound for centres in Lombardy, Tuscany, Emilia Romagna, Veneto and Marche, with around 100 remaining in Sicily, divided up between Messina and the mega-centre at Badiagrande in Valderice, which has a capacity of 200 people. Trapani has been crowned queen of reception centres, hosting around 3,000 people, many of whom are now employed picking grapes and, after a short while, will also pick the olives. Such centres are host to migrants arriving from all across Italy, increasing the landowners’ ability to push down the price of labour power.

The CIE [detention centre] in Trapani has still not been converted into a Frontex ‘hotspot’, and there are more than 100 North Africans who have been holed up in precarious hygienic and sanitary conditions for over a month, as witnessed by delegations of members of parliament and members of the campaign group LasciateCIEntrare.

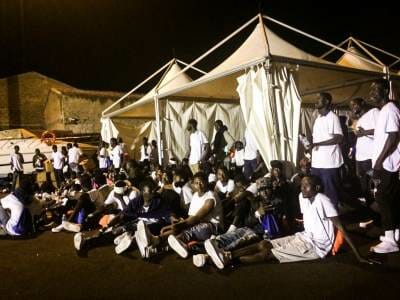

Around 780 people arrived in Palermo, all of them quite young, some very young, including five Eritrean children aged between 10-13 years, who arrived alone. In the end many minors were declared adults so that they could get on the coaches. The coaches themselves had arrived from Romania, not because of the quotas dreamed up by different European countries, but because the prefecture’s newly tendered contract for migrant transportation was won by the Romanian company Atlassib.

Another new development in the disembarking at Palermo concerns the distributed bag of essentials. This will no longer be managed for free by the charity Caritas, but instead by the supermarket group Conad. The volunteers from Caritas, given their experience, will take care of distribution until further notice. The provision of jumpers, shoes and trousers at the Palermo disembarking is to be managed by Play Sport, a company from Syracuse, itself no newcomer to such arrangements (they are present at Pozzallo, for example, among other locations). Therefore even Palermo, a city once characterised by the presence of some humanity, has been transformed into a market place, just as this system desires. Obviously the prefecture wouldnot have been adequate in the moment in which Caritas could no longer distribute food and clothing. Humanity is something which the managers of many centres for minors seemingly do not possess, judging by the coldness with which they came to the port to pick up their ‘merchandise’; and of course this just makes the young men’s journey ever more difficult, as they land up in institutions unprepared for their arrival, in which no one speaks their language, and in which the management imposes barracks-style rules so as to impose order. In one of the many trips made last weeks (in which we received still more complaints, and indications of unacceptable behaviour), we noted the regularity with which the verb ‘must’ was used to express the correct attitude. The possible consequences of the transgression of rules, as was so often recounted to us, are the confiscation of pocket money or psychological blackmailing. This is also the case in the highly specialised regional centres, in which the quality of services is supposed to be guaranteed. Instead, the criticisms are continually mounting up, from San Giovanni Gemini to Trabia and Alcamo.

The consequence of this is that minors run away, and can then be found on the streets around the station, sleeping in parks and doorways, largely because no one is able to explain to them how – and for how long – they need to remain in the centres, or even why.

An outspoken 16-year-old Eritrean teenager told us how he was beaten and tortured in Libya, including with an electric current, and that it was only after his parents sent blackmail money that he was released, a fate not shared by many of his companions. ‘I want to get to my cousin in Milan and I will do everything I can to make that happen, because my parents have given up their lives for me and my freedom. I don’t want to fail them, I cannot fail them, I want to live like a teenager of my age, I don’t want to wake up every night crying with the fear that follows you around and doesn’t leave you, I’m tired and too young. I’ve spent three months in a centre and done nothing, I just slept and ate, and I still don’t have any documents, so I’m making it by myself, I met a friend.’

We asked him and the others more questions, and the perception is that it is the absence of clarity, mediation, support and tutoring (and in many cases even of a tutor) which makes so many run away from the incompetences of the reception system, just like our Eritrean friend. He too will probably end up relying on those who exploit the possibilities which Europe provides them, profiting off these young men’s hopes and dreams.

On a basic level, we understand why minors declare themselves to be adults, for at least that way they have a route North via the Romanian company, which makes it easier to arrive half way, instead of ending up on the street and searching for that last speck of humanity which some people still possess.

Translated: Richard Braude