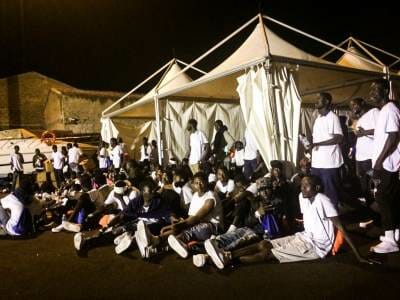

Visit to Serraino Vulpitta, the original CIE (Immigration Detention Centre)

by Alessio Genovese

The Centre’s former car park has been converted into a football pitch, but today it is deserted. The 41 “guests” are in the three sections on the second floor and are awaiting our visit. Today none of them can play football. Everything has to be kept under control as much as possible, at least for today- at least during the visit of the Pd (The Democratic Party) politician, the Honorable Alessandra Siragusa. On the first floor, the vice Prefect, an officer from the Trapani Police Headquarters and the Director of the CIE are waiting for us.

The first two rooms on corridor 14 are empty. Generally the “livelier” immigrants, those transferred from other Italian CIEs and those waiting to be repatriated are the ones who end up behind bars in isolation. In fact in the last few months, it is this CIE, Serraino Vulpitta in Trapani, that has become the place of transit for hundreds of irregular Tunisian migrants waiting to be boarded onto flights from Palermo back to Tunisia.

According to the Centre’s main doctor, appointed by the managing

Cooperative Insieme, the situation is

under control. The migrants who require specialised medical treatment or check

ups are sent to hospital in Trapani

and then returned to the Centre. “There have been cases of TB and HIV in

the past, but currently there is nothing so serious,” says the doctor. Yet

from looking at the migrants’ clinical records, we discover that in just the

first nine days of May there were 13 emergency operations. “It is always

the same two, Reda and Muhammad, every day, every day they have to be sent to

hospital,” says the officer from the police headquarters.

Reda is a nineteen year old. He comes from Marocco but grew up in Palermo, where he was

living with his mother. He has attempted suicide twice in the last month. He

can’t accept being kept away from his mother who lives alone and is in need of

care. Less than a month ago he was found with a sheet around his neck, hanging

from a beam in the bathroom. “It was 4 o’clock in the morning when we

found him,” Wilson, a young Albanian who has been in S. Vulpitta for 2 months,

tells us, “it’s a miracle he’s still alive. He was already unconscious.” Wilson doesn’t stop talking. He speaks perfect

Italian, which he learnt while serving a five year prison sentence, the maximum

that can be given under Italian law, for drug dealing offences. Now that his

sentence is finished, he has spent the last two and a half months locked up in

the CIE in Trapani.

“There are nights when I go to the bathroom and I feel as if I’m living in

a horror film. There’s blood everywhere. Here there are guys who slit their

wrists and eat glass and iron.” He continues, “They want to make you

think that here everything is fine, but the reality is much different. Reda has

been stuffed full of Rivotril, a tranquiliser, look in his eyes- there’s no

life there. A nineteen year old guy with no life in his eyes.” The first

day Wilson arrived at the CIE he said he wanted

to go home, to Albania,

to Valona. “This place is like hell, I want to go but I’m still here. Why?

Many of us are afraid to speak to you in front of the police, but I am

not. You know what the officer says when

these things happen?” Wilson

looks the agents who are escorting us directly in the eyes and continues,

shouting, “he says that if they try to hang themselves once, they’ll do it

again; if they’ve eaten 100

grams of glass they can eat 200. They make fun us, you

see. It was us who saved Reda. Here inside people can die, and they don’t give

a damn.”

The situation at Serraino Vulpitta

has already degenerated beyond every measure. The night between the 28th and

the 29th December 1999, the first CPT (Centre of Temporary Stay) in Italy caught

fire. (In the Turco- Napolitano era, what have now become CIEs were known as

CPTs and in August 1998, the first was inaugurated in Trapani). The blaze of

that night was started as a protest by one of the twelve migrant detainees. It

saw six people lose their lives. This happened over twelve years ago. Hundreds

of men have since stayed in the cells. Through the prayers and messages of help

written on the walls over the years, the cell walls know all the languages of

the world. Yet every night there is always the risk that someone inside will no

longer be able to leave such messages.

Even the Director of the Centre confirms that it is getting more and

more difficult to work in these conditions. The extension of the detention

period to 18 months has contributed to difficult situation, the repercussions of

which also fall on the men from the Cooperative and the police who are called

more and more often to intervene in attempted escapes and protests. Very often

such protests are triggered by the dire hygiene conditions and the poor quality

of the food. In the current climate of crisis and cuts, the more competitive

cooperatives are being favoured. The daily expenditure has fallen to around €20

per “guest”, which is surely not enough to guarantee a minimum

standard. The consequences are clear to see. During the distribution of today’s

meal for example, the Honorable Siragusa noted that on the vacuum packed trays

there was no label with the date of preparation or list of ingredients.

“If a lorry transporting food without these labels is stopped and checked,

the company would be closed down,” observes Siragusa.

The visit continues under the eyes of our escorts, the police, who seem

to be more concerned that we don’t take photos than anything else. The Centre’s

“guests” follow us like a type of improvised train. Each of them has

a story to tell us: relatives and friends who are waiting for them who they

want to pass information on to. Different stories with the single common

denominator of being found on Italian soil without the necessary documents. And

there are also the many who, like Wilson,

came to the Centre after serving prison terms. At the end of their sentence

they are transferred to the CIE, thereby having to serve another sentence, one

which is unjust and has no sense. The CIEs are for people who need to be

identified, those without documents for whom it is necessary to collaborate with

Consuls and embassies in their country of origin. They are certainly not meant

for people who have already been identified. And it is this same line of

reasoning that justifies the existence of these places, which have seen too

many scenes of violence and violation of rights. For us, such places must be

reduced as soon as possible. The fact that within the Centre the irregularity

of the migrants is controlled, is a physiological consequence of the way in

which these structures have been designed. Furthermore, it is not rare to find

people who have been persecuted or who are escaping war within the CIEs despite

the fact they have begun the asylum seeking process.

There is a group of five people who are separated from the others at the

end of a dark room. They are Egyptians who arrived in Mazara del Vallo on the

1st May aboard a fishing boat with a further 74 co-nationals. The only part of Italy

that they have seen are the walls of S.

Vulpitta where they ended up a few days after coming ashore. Nonetheless,

they have fared better than the majority of their travelling companions who

have since been repatriated, put on a flight from Palermo

to Cairo at

five o’clock in the morning. The operation was carried out in secrecy. They

were not even informed of their right to present their application for asylum.

Adel is one of the five who ended up in the CIE. He speaks only Egyptian

Arabic, “In Egypt, the situation is too dangerous for us. I am a Coptic

Christian and my family was threatened after getting involved in a fight with

the Salafists. They come into our quarter on the outskirts of Cairo and start shooting and terrorising the

residents.” Adel has a Coptic cross tatooed on his hand along with the

scars and signs of having fought with the baltagiya,

the armed gang who sow panic amongst the people. His four companions are Muslim

Egyptians and agree with what Adel says. They say, “We have also had

problems with the gang. That’s why we left. It’s too dangerous to go on living

there. The destiny of our families depends on this journey and on whether we

are able to find work in Italy.”

They have already made their request for asylum. They say it was the first

thing they were told to do on their arrival. But measures for their expulsion

have probably already been taken. How else would it be possibly to justify

their presence in a CIE? It is a procedure which remains within the limits of

the law that will keep them locked up for who knows how long.

Even now in a recent meeting at the Commission of Human Rights at the

Senate, the Minister Cancellieri continued to affirm that it is, “only

fair to highlight the fact that attention to the living conditions within the

Centres remains the main point of delicacy to which I am particularly

sensitive.” While the government is financing new CIEs and improvements

for those already in existence following the same politics of the previous

government, we have to raise our voices to request the closure of these Centres

because it is not possible for there to be dignified living conditions in

places where detention on administrative grounds can exist for up to 18 months

with the denial of the most basic rights.