The reception centres in the Madonie (Palermo) – Part 3

“We are human beings”

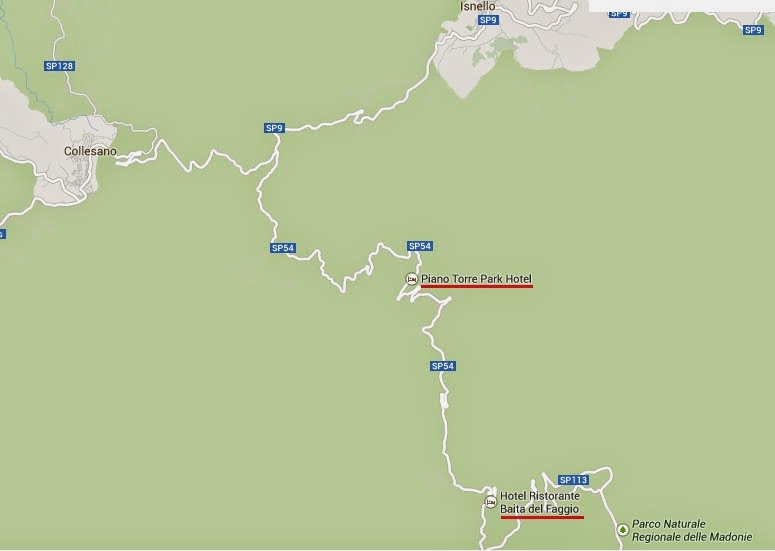

Apart from a wonderful and unspoilt countryside, numerous animals and lush vegetation, there are two facilities in the Madonie that are used as collective reception centres: Baita del Faggio and Piano Torre Hotel. When it opened in December 2013, the management had been transferred to Parrivecchio SRL. In May, a transfer in favour of cooperative Scarabeo took place. Both centres are difficult to reach due to their geographical location. Once you get there, it is still difficult to perceive the reality

because of contradictory and imprecise statements of those who live or

work here. I went there twice with the aim to better understand and to

connect the different versions as good as possible.

Both the cultural mediators, who greeted me the first time I went there, as well as the person responsible for the management, I encountered at my second visit, insist that the two centres are CARAs (collective housing for asylum seekers). In reality, there are common CAS (extraordinary reception centre).

Baita del Faggio: The facility is currently closed. The mediator describes the centre as a temporary solution (for a period of several months) for the very first reception. He tells me that groups with many migrants were transferred here immediately after their arrival. He also tells me that 200 Eritreans once had disappeared in the Baita during the first night of their stay. The other employee tells me, however, that the centre is closed only at the moment. The reception in the Baita had been suspended because of a missing document. I ask whether the escapes where the reason for that and she replies that once a teenager ran away to go to Germany but he came back shortly after.

Hotel Piano Torre: Since about 3 months, the centre accommodates 43 young men of various nationalities (Mali, Senegal, Gambia, Sierra Leone etc.)

Up to now, the young men have been brought to Palermo for medical examinations. However, for visits to the GP, they are looking for a way to establish a relationship with Cefalù. So far, the physician went to the centre once or twice a week. During my second visit, I am told that they are getting the last STP ready as some migrants did not have any health problem in these four months. (STP = Temporarily Present Foreigners; a coded ID which is given to the foreigners who cannot enrol at the National Health System because they are staying illegally on Italian territory).

In terms of the food, I am assured that they follow a balanced diet: rice and side dish for lunch, meat and side dish in the evening. The dishes are cooked in the centre. This way, the freshness is assured. The migrants confirm that they practically eat unseasoned rice and lots of potatoes every day. Meat, if it goes well, once or twice a week.

The clothing is collected from an informal network of acquaintances in the church and from private persons. Only part of the garments that are handed over to the employees, are given to the migrants. The staff explained that the donated clothing often is too big or too small and that young men sometimes refuse to wear clothes for girls and the elderly. The version of migrants is different: the employees reward the quietest persons with clothes and withdraw them from those who protest.

The pocket money is € 2.50 per day. The young complain being ironic about the fact that they live in the bush and cannot use the pocket money. They mainly use the money to buy cream, cigarettes and razor blades in the centre. The employee tells me that they bring tobacco and cream and sell those directly at the hotel so that the refugees do not need to go to the village.

The nearest town is 9 km away along a winding road surrounded by trees. You need a quarter of an hour by car if driven 40-45 km/h. When walking, the distance seems to be endless. The refugees may go out from morning until evening, as in any other CAS, but where should they go? What should they do? The migrants told me several times that they feel like being in prison. “We are human beings,” they say that as if someone questioned this. They tell me that wild animals try to get into the facility at night attracted by the smell of the food. When I left the hotel at night, I come across two wild boars. The migrants want to be relocated; this concern goes far beyond the need to get the papers. “Even if I get the documents, what am I doing with them here? Show them to the trees?“ an asylum seeker asks.

The migrants do not trust anyone. They are convinced that the police, administrators, staff and the owner of the hotel act with the intention to let them live in discomfort and deprivation. It seems to me more likely that the migrants’ are the last thoughts of those who actually determine their fate. In spite of that, maybe the belief that a few are worthy of the cruel attentions, these young men feel less distant and forgotten by the world

They tell me how they tried to take their concerns to the outside. On 18 August, 33 migrants went to the police of Isnello for the first time. There, they were promised to be transferred. The relocation of 33 persons was actually planned by the end of the month but was carried out by Baita del Faggio where 36 people are housing: 33 were sent to northern Italy, two of them were minors and, therefore, transferred to appropriate centres, one immigrant got relocated to Piano Torre. According to the migrants of Piano Torre, the relocation was actually intended for them but the administrators of the centres preferred to get rid of the most undisciplined, the young people of the Baita. They returned to the police station on September 3 to protest. This time, without any success. The police just told them, “Oh, you’re still here”.

The migrants tell me they were quiet at the beginning. To give me an example of how they had gradually lost trust and patience, they tell me the following event. When they arrived, they have been told that if they cleaned the pool, they could use it. However, after they had cleaned it, they were only allowed to take a bath once. The employee says “correctly”, because the pool does not belong to the service provided. To justify herself, she explained that it was the owners who manage the hotel and that the organization Scarabeo had no right to use the swimming pool. And then she realizes that without a lifeguard nobody could swim in it. This was not explained to the young men before they made it usable again. The migrants even top it up by telling me that they had the feeling of being fooled twice when they saw that the tourists paid to use the pool that they had cleaned. Tourists? During my second visit, I ask the employee whether the facility is also used as a hotel or restaurant. She says no. I ask the migrants again, “Guys, what’s going on? The staff tells me that there are no tourists here.” They react perplexed and say that he tourists often stay at the hotel and use the pool. They tell me that it is not allowed to be at the pool or to reside in the community hall when tourists are there. You are going to call “Mamma Sara” (the person responsible for the management) and ask her to repeat their version in their presence. Sara slowly remembers. First, she admits that people were here for lunch. Then she explains that guests sometimes stayed at the facility during the afternoon and used the pool. After some hesitation and the pressure of the migrants, she retreats and confirms that a football team came to train and stayed overnight. But she hastens to point out that she has nothing to do with it: the owners are responsible for the use of the facility. The young people present me this change of opinion as evidence: what managers say should not be trusted. We learn nothing about the intentions of the people but the passing of responsibility between cooperative and owners of the facility suggests that there is little transparency in the management of the centre/hotel management.

Before I leave, a young man, who was standing aloof during the conversation, approaches me. He tells me strictly to help him. The tone of his voice is almost threatening. The motivation he has is different from that of the others. He says he has health problems and the doctors just pretend as if they would heal him. I ask him to explain more clearly, and he adds, “Since I arrived here, I feel things under the skin that stings me. The doctor gave me an ointment that I should apply for a few days. I did that, but it has not changed. They examined me but found nothing. But I sense there’s something in me that stings me under my skin.” I can only imagine that it is a psychosis, apparently untreated. The day after my second visit, the police came to the centre and promised that everyone would receive a residence permit for 3 months within 20 days. The young people urged to reaffirm their priority for the third time: The need to be relocated.

Carlotta Giordano, Borderline Sicilia

Translation: Aylin Satmaz