The Politics of Criminalization of “Smugglers” and the Sacrifice of Human Rights

Article first published on February 18, 2022

Meltingpot.org – In “From Sea to Prison”, an analysis of the challenges faced by accused smugglers seeking a fair trial.

On October 15, 2021, “From Sea to Prison: The Criminalization of Boat Drivers in Italy” 1, a report curated by ARCI Porco Rosso and Alarm Phone with the collaboration of Borderline Sicilia and borderline-europe, was published.

In this secondary study we deepen the focus on the challenging legal procedures endured by those accused of smuggling. The first part is available via this link (Italian language).

A difficult trial

A discussion of the issue of unregulated immigration is complicated because it requires analysis of a complex phenomenon that is easily subject to political and ideological prejudices.

Immigration is a structural phenomenon that is not unique to our time, and that demands a multidisciplinary approach that is not always easy. Within this complex phenomenon there are decidedly more difficult issues to deal with because they suffer more from political prejudice and are liable to be misunderstood. One of these themes certainly concerns the figure of the so-called “smugglers.”

The report “From Sea to Prison. The Criminalization of Boat Drivers in Italy” addressed a particular aspect of the migratory phenomenon by concentrating the analysis on the shifts introduced by Article 12 of the Immigration Consolidation Act by Law 189/2002 (the so-called “Bossi-Fini Law”), which introduced the criminal theory of “aiding and abetting illegal immigration.”

This analysis serves not only to provide data on the phenomenon, the crimes and punishments, but above all to shine a light on a topic that often seems self-evident.

From this point of view, it is worth noting that there are many lawyers who have spoken out on the complexities of facing an open criminal case for an accused smuggler. “A difficulty linked to the fact that these processes are politically conditioned: in the hunt for the smuggler, a scapegoat to bear full responsibility, normal procedural guarantees are abandoned and those principles on which every criminal proceeding should be based are swiftly violated.”2 The accused often face trials against very aggressive prosecutors that seek inordinately high sentences, up to life imprisonment. The alleged smuggler is charged with universal guilt of illegal immigration and shoulders all the blame for the victims of the crossings.

Foreign smugglers, destitute and often without any known connection where they land, are a vulnerable link in a larger network and it is difficult to imagine that a voice could be raised in their defense. A courtroom trial, then, becomes an ideal stage upon which to send a political signal via the punishment of the “smuggler.” The accused, once identified, is effectively isolated and marginalized. This treatment forces before them an obstacle to accessing their fundamental rights, to a fair trial in compliance with constitutional principles on the subject of punishment.

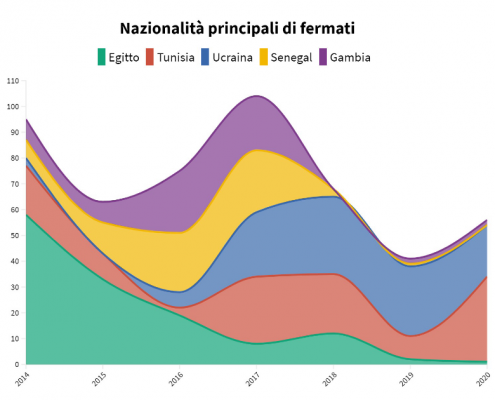

Main nationalities of detainees

Main nationalities of detainees

The role of the defense

The report demonstrates that the right that is anything but taken for granted by a person accused of being a smuggler is the right to a full and effective defense.

The Italian law prescribes that in the criminal trial a person accused of a crime cannot defend his- or herself alone but must have recourse to a defender. When a suspected person does not choose a specific lawyer, a public defender is appointed. Furthermore, when a person does not have the economic resources to support the costs of a defense, they can resort to the institution of legal aid. On the basis of this system designed by our legislation, the right of defense is ensured, at least formally, equally by a trusted lawyer and by an official, both for those who have economic means to support the costs and for those who do not have such means.

The reality, however, is quite a different picture: “A selected lawyer is dictated by their knowledge and experience in a particular area of criminal law, their professionalism, as well as their particular ability to understand the client. A state-appointed defender, on the other hand, has no relationship or previous knowledge of the client, challenging the establishment of trust between the parties, and posing the risk that a lawyer will be appointed with little, if any, experience in complex processes such as those for aiding and abetting, with serious consequences regarding the effectiveness of the assisted person’s right to defense.”

This issue becomes all the more pertinent given that those accused of smuggling are, in most cases, defended by an appointed lawyer and resort to provided legal aid. This condition almost inherently determines a power imbalance between the prosecution and the defense. A defense in such complicated trials as those involving people accused of the crime referred to in art. 12 TUI* requires close teamwork, and the defender must often be assisted by interpreters and specialists to carry out adequate defensive investigations. All this naturally requires specific professional preparation and the availability of economic resources.

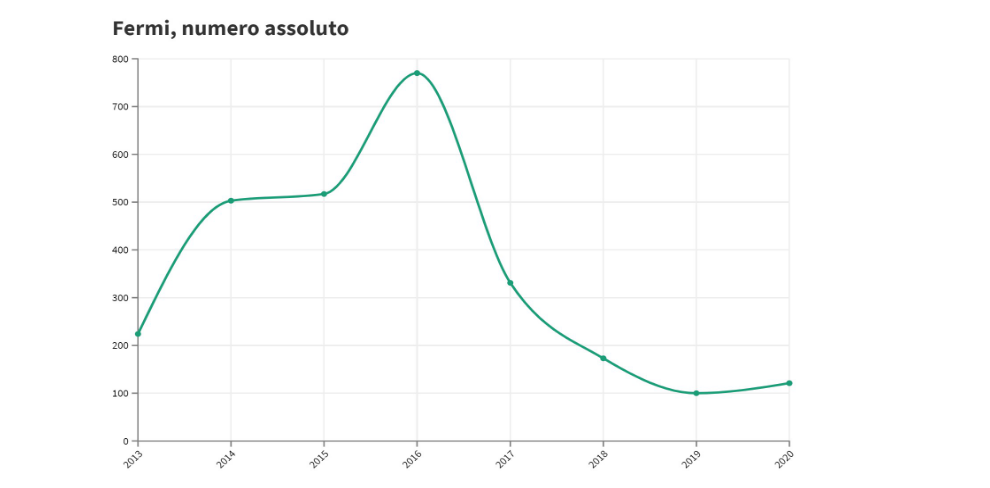

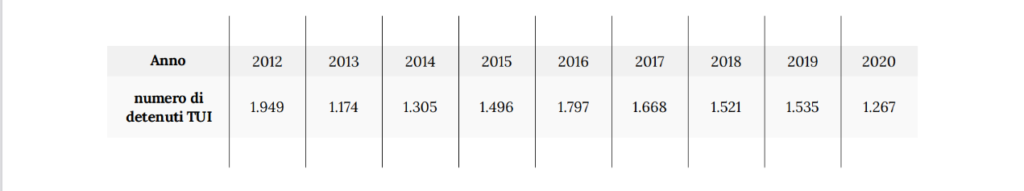

The total number of those arrested in the last 8 years is 2,559.

Defense strategies

In the trials against alleged smugglers there are various strategies that a lawyer may adopt.

a) Collected Testimonies

The first action of the defense consists in verifying whether there have been procedural errors committed by the prosecutor or the police. At this stage, the analysis of any evidence collected is central for a defender. Passengers heard during disembarkation, in fact, are also responsible for the crime of illegal entry into Italy (so-called “clandestine entry”), and therefore must be considered persons under investigation for a crime connected to that of the alleged smugglers to be heard by the police with the assistance of a lawyer, according to the due guarantees of the law.

Furthermore, testimony given by witnesses must be examined carefully for possible ulterior motivations, primary among these the promise of a residence permit in exchange for their participation in the trial.

b) Self-aiding and abetting

In the course of various proceedings, it was argued by the defense that art. 12 TUI* cannot be applied to the aiding and abetting conducted by one of the migrants involved in the episode of illegal entry in favor of their travel companions. This is typical in a case of a group of migrants abandoned by traffickers in the last miles of the journey that reaches the Italian coast on a boat they drive. In order for the offense of aiding and abetting to take place, there must be a separation of roles between the one who grants illegal entry into the State and the one who is granted the same entry. In other words, the aided migrant cannot coincide with the aiding subject under investigation.

c) State of necessity

The Italian law provides that a person, even if they have committed a certain crime, cannot be held guilty when they have been forced to commit it in some way. Therefore, if a person drives a boat to save themselves or others from serious and unfair harm to the person, they should not be considered guilty because they did it out of necessity. It is here, then, that if the defense can prove that the migrant has been threatened or suffered violence for being forced to drive, the state of necessity is deemed to exist and the accused acquitted. With the sentence of the Court of Palermo in the person of the GIP* Gigi Omar Modica, on September 8, 2016, for the first time the state of necessity has been recognized as a justification for two people accused of being smugglers who had declared that they had been forced with physical violence and threat of death to drive the boat.

Foreigners currently represent 32.5 % of the prison population (page 69 of the report)

Conclusion

The report, therefore, carries out a careful analysis of the ongoing criminalization of the so-called smugglers. The phenomenon has directly affected 2,500 people in the last 8 years; people accused of having played a decisive role in the transport of migrants to our country.

The report’s conclusions highlight that the political objective of persecuting the “smuggler” at all costs enables the justification for violating the most basic human rights – rights that are set aside in preference of identifying a culprit, as follows:

- Methods for identification are often extremely approximate;

- access to a full and effective defense rarely guaranteed;

- Even a noticeably weak preliminary investigation can be enough for an extremely heavy sentence;

- As with foreign prisoners in Italy more generally, the life of boat drivers in prison is still harsher than for other prisoners;

- The effects of criminalization continue even after the conclusion of the criminal proceedings, in that a guilty verdict blocks recognition of international protection.

Lawyer Arturo Raffaele Covella

* TUI: Testo Unico Immigrazione – Immigration Consolidation Act

* GIP: Giudice per le indagini preliminari – preliminary investigation judge

Translated from Italian by Olivia Taibi