The Difficulties of the Reception System in Trapani

Requests for help have been coming in from people hosted in reception centres across Sicily, but over the past month such messages have been particularly concentrated in the province of Trapani. We understand this to be due to a number of factors, first and foremost the new contracts which have recently become active, and which have been awarded to entities with little experience in the reception business and cooperatives which have attempted to expand their activities by taking on several structures simultaneously (Extraordinary Reception Centres* as well as centres for minors and ones run by the central service in Rome*).

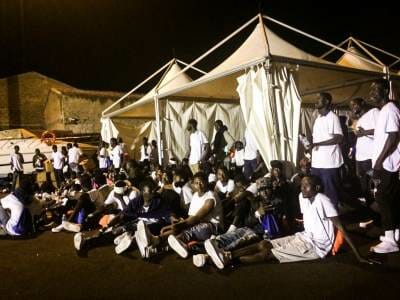

Young migrants in the Extraordinary Reception centre ‘Essarasya’ – San Miceli (Province of Trapani)

There is currenly a vast mass of people who have come to the province to work in the countryside, including the olive harvest, competing with those who have been in the area for some time. As we have emphasised many times in the past, local institutions have done nothing to protect the workers, instead enacting solutions which favour the repression of the invisible masses and embolden the landowners.

Oppression and exploitation are the watchwords of many reception centres, which considered not so much as locations to interacts with the surrounding area but simply containers in which people who have arrived by sea with only the shirt on their backs can be “deposited” for long periods of time, far from indiscreet eyes.

The majority of the Extraordinary Reception Centres (CAS) which have been opened (in the province of Trapani as well as elsewhere) are hidden, far from residential centres, reflecting a clear political choice: not seeing Blacks wandering around allows for the centres to be opened, maintaining business ad a sufficient level without creating problems for the area.

The Prefecture of Trapani is directly to blame for this, inasmuch as it is the body which is meant to monitor the area and ultimately decide whether a centre is appropriate or otherwise. Such is the case with the ‘Essarasya’ CAS in San Miceli, which we had the opportunity to visit around a month back. The building is surely ideal for us as a resort of agricultural tourism centre, but entirely inappropriate as a CAS, given that it is far from the town of Mazara del Vallo, behind an electricity station and reached only via a small, unlit road, extremely dangerous for anyone travelling by bicycle or on foot. The manager opened the doors and spoke to us with freely, despite the fact that the quantity of critical issues we had heard about, supported by photos sent by the residents over the previous days. These complaints cannot all be blamed on an institutional stagnancy, but also on a lack of attention by those who manage the centre itself.

The cooperative, part of the consortium “Umana solidarietà” (in a period of marked expansion in the province of Palermo as well) also manages another CAS in Marsala which has been closed down in the past following an inspection by the Prefecture. The cooperative had to undertake extensive restructuring work on the building in order to continue its activities, and we could see that the structure has been newly done up, given that the San Miceli CAS was opened on 20 May 2017, with an agreement for 50 places which expires in November. A month ago, during our visit, there were 44 residents present, asylum seekers originally from, for the most part, West Africa and Bangladesh.

The complaints arrived to us some time ago, along with a photo showing a group of people with a sign on which they had written the problems they experience in the centre, and we tried to verify these with the manager, who confirmed that there were indeed some problems in communicating with the residents.

The young men themselves expressed their refusal of out-of-date, monotonous food: “We have eaten the same things at lunch and the same things at dinner ever since we got here, and sometimes we’ve even thrown it all away because it stinks. We all have digestion problems and we’re lost weight”. To support this thesis, ‘M’ showed us a photo of when he arrived at the centre. We suggested a meeting to create some kind of mediation between the residents and the managing body, but at the time of writing this has still not happened.

A further problem that demonstrates the logistical difficulties is the activation of a basic Italian course within the centre, which has been absent since July, as the cooperative has not been able to find a solution since the only worker who carried out the only contractual activity within the CAS resigned. Till today, the young men in the CAS do not go to school because, despite their enrolment in the adult education centre* (in recent weeks), the lessons have not commenced and the complaints continue every day.

Another critical aspect is the waiting times for documents: at the time of our visit, only six of the residents had filled out the C3 form, while the others are slowly being invited to the police station in groups of six at a time.

Another problem indicated to us related to the lack of working air conditions, meaning that – due to the intolerable heat – people are forced to sleep outside, in the centre’s hallway, and consequently were bitten by mosquitoes and other insects throughout the entire Summer. The manager confirmed the resident’s narration, claiming that the air conditioning has never functioned due to work on the electrical circuit which was only completed very recently.

Still further problems have arisen due to the lack of water on some days; there is a water truck in the area which comes to fill the centre’s tanks. Sometimes there is no hot water. Given that there are solar panels installed and on some days it rains or the sun simply does not shine (fortunately only a few days in these months), the manager ought to organise gas heating.

Finally, many of the asylum seekers say they do not feel there is adequate protection from a health point of view, because the medicines are insufficient. We reported this complaint to the manager, who emphasised that the young men are cared for, and always assisted from a medical point of view through the presence of a doctor in the building once a week, and a nurse who has a supply of medicine in the centre.

A month after our visit, the situation has not changed, even if the staff are trying to patch up the problems. The residents are still waiting for Autumn clothes, given that they are still wearing those they were provided for in the Summer, when they first came to the centre. They have, however, received blankets. The most serious issue, however, remains that of communication, because aside from one worker who is always present at the centre and speaks a little school English, they have no real point of reference. The managers are rarely present and the official mediators, the residents claim, no longer work at the centre, and have been replaced by a new mediator who – again, according to them – does not have her predecessors’ skill. In sum, there is no point of reference, there is no relationship of trust with the managing body, and they lack any response to the questions they have about that awaits them.

Such a state of limbo obviously leaves people feeling uneasy and, at times – along with other problems in the CAS – has led to protests and conflict, and we have heard about many such episodes across Trapani over the recent period. They began in the Summer when the ‘Aerus’ CAS in Triscina was closed by the Commissar of the local council of Castelvetrano, due to the inappropriateness of the buildings.

The former agricultural tourism centre ‘Sicilia 1’ in Castellammare del Golfo was also closed (both of these are CAS which we have heavily criticised in the past). At the ‘Ericevalle’ CAS, however, a host of people had their right to a place in the reception system removed and were kicked out: as usual, those who pay the price are people who reach their breaking point under the pressure of a future which seems gloomier with every passing day. People who, having already seen death walking beside them, continue to live in difficult situations which often eventually become the last straw. Unfortunately, such people’s vulnerability is never monitored or taken on board, partly because the CAS system does not include such a level of attention.

The protests have not only hit the CAS, but also the centres run by the central service in Rome.* The most recent episode took place at the centre in Alcamo, run by the cooperative Badia Grande: a Senegalese man was charged with resisting arrest and attempted extortion after having lost his temper over a missing transfer of €45.

Finally, the Prefecture carried out an inspection of the Sataru CAS in Contrada Fraginesi, near Castellamare del Golfo – another isolated location – in which they found a range of infarctions of the rules and complaints by the residents. Some of them have since been transferred to other structures in order to reduce the pressure on the managers and provide an opportunity for them to make the necessary changes: a working method adopted by a Prefecture that prefers not to immediately close a centre but instead provide some indications for how to continue in the sector.

As is obvious, as usual, in these difficult situations the price is always paid above all by the migrants themselves, who suffer from deficient and inadequate Italian reception policies.

Alberto Biondo

Borderline Sicilia

*Extraordinary Reception Centres = Centri di accoglienza straordinaria

*the central service in Rome = Servizio di protezione per richedienti asilo e rifiugiati

*adult education centre = Centro provinciale per l’istruzione degli adulti

Project “OpenEurope” – Oxfam Italia, Diaconia Valdese, Borderline Sicilia Onlus

Translation by Richard Braude