No Longer Human

We publish below a contribution from a humanitarian worker

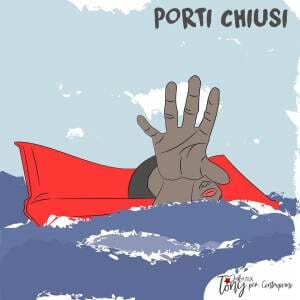

June 10th of this year marked a moment of change for Italy and Europe in terms of their joint relations and for the management of migration. Italy said “enough”, we’re no longer allowing foreign ships to enter our ports. And between diplomatic incidents, institutional mistakes and wasting of public funds, the death at sea has simply increased.

The decision to not authorise the entrance of foreign vessels into Italian ports is coherent with a general climate that you can feel for some time in our country. Discriminatory and xenophobic feelings – recognisable in the various partisan slogans brought us to the election of an anti-immigration government, as well a populist anti-European one – are sharpening and spreading out over the past days, splitting Italy in two. The many demonstrations and protests that have taken place across the country have seen two opposing factions in the space of a few metres, revealing the true face of Italian society. A nation broken in two, disoriented. #Welcomerefugees on one side, #chiudiamoiporti (“close the ports”) on the other.

The problem apparently is that “we can’t take all of them”. Europe has abandoned us, it always had, here we have our own problems and we can’t take on board all the problems of Africa as well. The images of people trapped in the Libyan detention centres have not sufficed to change people’s minds. “Italians First”.

Above all, it must be remembered that closing the ports does not mean simply taking a position in relation to other European states. The Italian government’s actions – in line more with a populist electoral campaign than any sustainable political program – puts the lives of individual persons at risk, and violates regulations of both Italian and international law. Italian anger can explain but cannot justify the decision to block our ports in the face of people looking for protection.

What right do we have to do this? None. According to international norms, the country entrusted with the coordination of rescue operations also identifies a place of safety in which the rescued persons can be landed. This principle has been repeatedly defended in the case of the rescue operations effected by the Libyan Coast Guard until a few weeks’ ago, but now the European governments have taken a step backwards.

The idea that resonates from the many political statements and ricochets from one newspaper to the other is that our duty is save lives at sea but not to host them, an idea without logic or rationale: the thousands of people who land on our coasts have experience abuse, violence, physical and mental suffering. Saving them means taking care of them. Forcing such people and the crews to confront long journeys, in unstable weather conditions and with few resources is not and cannot be a true response.

The Aquarius finally arrived in Valencia yesterday, both the Italian and Maltese governments having refused to assign it a port of safety. The migrants rescued by them – 620 people divided between the vessel of the NGO SOS Mediterranée and MSF, the ‘Dattilo’ of the Italian Coast Guard and the naval vessel Orione – include pregnant women, children, people in need of protection, medical care; closing the doors of Europe to them means reneging on a basic principle of respect for their right to life, aside from international law. Those who maintain that a few extra days on board cannot in any way threaten their physical or mental health defends an idea based on the fact that they are not there at sea with them. Nights in the dark, scarce food supplies, the reduced quantity of medicine and medical staff, the freezing cold or unbearable heat, the fear – these are all conditions that challenge, wound and humiliate the hope and humanity of those who arrive here with the single desire to live a better life.

Nevertheless, Brussels has decided to triple the funds for border and migration management. The proposal brings the current 13bn up to 34.9bn for the years 2021-2027. It remains to be asked what exactly these funds will be used for, and if the costs dedicated to the closure and externalisation of the borders will truly resolve the problem or simply put more human lives at risk. All the precedents are already there: it is enough to recall the “Fund for Africa” established by the previous government, that instead of supporting development in countries of origin, has simply filled the pockets of military generals and tribal leaders in Libya.

Thus, following the rejection from Malta and the availability o the Sànchez government, the Aquarius has found a place of safety in Valencia. And hear the hypocrisy and calculations of the Italian government emerges again in the decision to employ two Italian navy vessels to support the navigation of the Aquarius, implying a consistent use of state funds, tens of thousands of Euros every day of navigation. Almost as if to say: we’re happy to pay in order not to take them.

And yet Europe has in fact always given us money. As one can read from the site of the Italian Coast Guard – to give an example – the requests for financing presented by that body and positively evaluated by the European Commission, only for the years 2016/2017, amount to more than €27 million. Money allocated exclusively for Search and Rescue operations and which no one – not even the Minister of the Interior – can use in any other way.

But there are those who say that Salvini has sent a strong message to Europe and resolved the problem of the NGOs in the Mediterranean. In fact, there will now be very few foreign vessels left to carry out rescue operations, with the fear of being blocked for days or weeks at sea, putting the existence of hundreds of human lives in danger. And while the few Italian ships remain the only to have authorisation to dock in Italian ports, making the journey between Sicily and the Search and Rescue zone off the Libyan coastline, people will keep dying at sea. The case of the USNS Trenton in particular provokes anger and rage, forced to abandon 12 bodies at sea, people who died after a shipwreck, and of the 46 survivors who shared a similar experience to those on board the Aquarius.

Inasmuch as I am directly involved in and witness to the current moment, I am asking myself what defense we will provide when history comes to ask us to provide an account. How our country will respond to the accusations of the violation of fundamental human rights. How we will live with the awareness that our hands are dirty with the blood and salt of the Mediterranean.

Finally, I wonder what I will say to future generations about my experience, as an Italian citizen and as a woman on board these ships. I will say that despite everything we still tried to keep up the hope in a better future, that we managed to remain human even if politics no longer has humanity, that we will manage to find alternatives and adopt a critical attitude towards this populism and demagoguery, that we are managing to defend the highest value on which our existence is based and in which we believe: life.

A humanitarian worker

Project “OpenEurope” – Oxfam Italia, Diaconia Valdese, Borderline Sicilia Onlus

Translation by Richard Braude