Caltanissetta: At Villa Amedeo, meeting the new residents of the CAS on Via Niscemi

We continue with out

monitoring outside the welcome centres in the province of Caltanissetta. The

choice of monitoring outside the centres is a direct consequence of the authorisation

by the prefecture, which includes conditions which we find unacceptable and

in contrast with our association’s primary aim to safeguard asylum seekers’

rights.

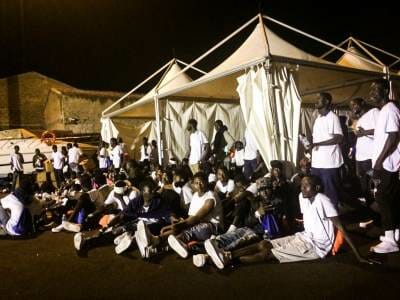

Thus last week I met with

residents at the Extraordinary Welcome Centre (CAS) situated in Via Niscemi,

next to the public park of ‘Villa Amedeo.’

We visited the centre in

question last year and found a very critical situation. We spoke about

the centre again following a protest by the residents last January.

CAS on Via Niscemi has been

open since 2014, housed within a building owned by the Ministry of

Telecommunications, which was given over for use by the welcoming system. Since

then it has been managed by a cooperative called ‘Vivere Insieme’ (which also

manages the CAS housed in the former IPAB complex in San Cataldo), which

originally operated with the prefecture’s backing. After the contract was put

out to tender it was constituted into a temporary business association (ATI)

along with all the other managers of CAS in the province.

There were over 20 asylum

seekers from the centre present at the meeting, and they immediately began to

list the major problems through which they live every day. First of all they

showed us that their toothpaste had expired. Some of the tubes, in truth, did

not have a date of expiry, but in one case where there was a date, it was from

2006.

They then talked about the

food served there, described as gone off and not enough. In particular, they

said that in the mornings they are served watered down milk and sometimes even

this has gone off. They described the bread as ‘like stone’.

They have made several

attempts to complain about being served inedible food, some of which

turned into actual protests outside the centre, but it was all to no avail.

Now, when they are continue to ask those responsible to make some changes, the

answer they’re given is that whoever isn’t content with the food can leave the

centre, given that there are hundreds of asylum seekers waiting to receive

welcoming services.

This ‘intimidating’ mode of

operating adopted to respond to complaints seems to be a deliberate practice

formed within this centre (as in many others). This kind of response, according

to the residents, is repeated every time some kind of problem is raised, and becomes

an actual threat when those responsible ask for names and surnames of those who

are making the criticisms and, noting down the names, imply that there will be

negative consequences at the Territorial Commission, or that the consequence

will be a long delay in waiting for the Commission hearing, or even that they

will take measures to remove them from the centre. All of these would have

negative repercussions on the Commission decisions.

“If you make problems, then

we will make you wait longer for the Commission”, or, “I’m going to denounce

you to the Commission”. These are just some of the responses which the

residents have received in answer to their requests, as recounted to us.

Yet again we witnessed the modus

operandi of managers who maintain their control in the centre by resorting

to a petty psychology of terror, entirely at their own discretion, accountable

to no one. Moreover the Italian government, despite almost entirely relying on

extraordinary centres for ‘first welcoming’, has still not provided any

systematic and functioning organisation body for their oversight. And, as the

prefectures are delegated with putting the welcoming system out to tender,

there is still no kind of necessary or meaningful supervision over the

management of this kind of centre, run anywhere and by anyone.

What comes into play here is

another peculiarity of CAS: economic accountability with a lot of scope for

discretion. This derives from many of the managers of these centres, being

primarily hotel entrepreneurs, managers of B&Bs and cooperatives which they

have established specifically to get into the welcoming business, operating

mainly for profit and so, wherever

possible, cutting the services and goods provided for in the tendered contract,

without incurring any consequences, simply because they are not obliged to show

how they have spent the funds which the government has provided, and which

services have been guaranteed.

And so we see it is not only

through offering off and inadequate food that spending can be cut and profits

increased. One can also in fact cut the basic quota allowance which is

distributed to the residents once a season. Clothing has never been distributed

in this centre. The residents informed me that recently 40 of them (of 65

resident in the centre), after around

months of being there, have finally received shoes.

Sticking with basic

consumption, the residents told me that they only have drinking water for one

hour every day, the only moment in the day in which a filter for water

purification is connected to the taps, which is then removed again after the

hour is up.

Clearly the main cuts are

those made to the personnel provided for the residents’ assistance.

According to the centre’s

residents, the currently employed are the cleaning lady, the janitor, two

Italian teachers and a social worker, who is nonetheless only there from time

to time. None of the workers, including the director of the cente (currently

the only person with whom the residents can ask for assistance), speak their

languages, nor any mediating languages.

Apparently, until June, the

centre employed a range of workers and linguistic-cultural mediators, some of

whom resigned after not having been paid for months, while others resigns after

having been put on forced holiday throughout Ramadan, during which the director

decided there was no need for any workers to be present, save for the basic

team.

Consequentially every kind of

assistance is lacking: there has been any legal information, nor is there any

psychological assistance.

There are, however, regular

Italian lessons, two hours every day for four days a week. The rooms have space

for 2, 3 or 5 people, and at the moment are extremely hot, but the director of

the centre didn’t want to buy any fans, and some of them have provided their

rooms with fan themselves, purchased with their pocket money which is

disbursed, if not punctually, in cash.

Health assistance is provided

by a general doctor who comes to the building every Monday between 8.30 and

9.30am. Beyond this weekly visit, the resident tell me that there is no worker

in the centre to call in case of any physical problems, and that there are no

medicines in the centre, not even sterile gauze or bandages. At night there are

no workers in the centre, and in case of any emergencies the residents call an

ambulance.

The situation at this centre

provides a good picture of practices throughout the entire system of first

welcoming. This is because the logic of emergency by which the government

continues to operate excludes any systematic oversight over the personnel to

whom this work is entrusted, leaving plenty of space for financial speculation

and organisation incompetence, always to the expense of those whom the system

is meant to guarantee protection.

Giovanna Vaccaro

Borderline Sicilia Onlus

Translation: Richard Braude