Those Who Die, Those Who Arrive and Those Who Remain: The Overcrowded Hotspots at Pozzallo

“What

Europe just doesn’t understand is that for migrants arriving in Libya

it’s less risky to try and escape across the sea that to try and go

back to their home countries”, says A., a young Senegalese man who

arrived in Italy two years ago. Like many of his countrymen, he’s

following the rescue operations on the TV, shot through with a sense

of momentary relief between the

powerlessness and rage. “Anyone who hasn’t been

in Libya cannot imagine what it means to live there. Every European

has a mobile, in the same way every Libyan, however old, walks around

with a gun in his hand. But no one in Italy wants to hear about

this.”

The merchant vessel OOC Jaguar at the port of Pozzallo. Photo: Lucia Borghi

In the

past few days the media has reported the news of the huge rescue

operations and arrivals: more than 13,000 migrants landed in a few

days on the coasts of Sicily, Calabria, Sardinia and Apuly, along

with the corpses of those who did not manage to finish the journey.

Very few words have been spent in asking why there has been such a

huge upturn in arrivals; there have, perhaps, been too many photos

and videos and a constant search for the most sensationalist news

which can be spread so as to record these dramatic moments, without

any appropriate respect for the privacy and suffering of others. In

general, the spotlights are switched off even before the migrants

have set foot on dry ground, to be switched on again with the next

instance of violence which can stir up public opinion. The elevated

number of rescues immediately carries us to a discussion of the

difficulty in managing the reception system: the new diplomatic

agreements, the increase in the brutality and detentions in Libya,

which has presumably blocked the departures till recently, is not

considered worthy of space in the daily papers.

And

thus it is that navy vessels, merchants ships and humanitarian

organisations have undertaken dozen upon dozen of rescue operations

in a few hours’ time. On August 24th

a new agreement was struck between the military mission Sophia and

the Libyan coast guard, projecting the training of the latter by

agents from the Eunavformed operation. This is the same Libyan coast

guard who have been attributed with the assault on MSF’s vessel the

Bourbon Argos, which took place on August 17th.

The attack was preceded by shots fired at standing height, and which

brought about a continuing stop to the ship’s rescue operation. The

agreement with the Libyan coast guard reflects the political will to

increase rejections and deportations, and the general strategy of

stopping migrants at the European borders, a strategy in which

European governments are engaged far more than any attempts to

provide protection to those who are fleeing.

This

political will has been confirmed by the EU Vice-Commissioner Frans

Timmermans who, on the occasion of yesterday’s meeting with the

citizens of Syracuse at the Greek amphitheatre, responded to various

questions about immigration by reaffirming that Europe’s challenge is

to “help them in their own countries”, protecting its own

borders, distinguishing between economic migrants and refugees, using

an iron fist against those African countries who do not accept the

agreements for readmission, and the impracticability of any

humanitarian corridors. The Vice-Commissioner also defended the

agreement with Erdogan’s Turkey. There was a great deal of rhetoric

about how wonderful the Italians are at welcoming, but not a single

concrete word about how to change the Dublin regulations, nor even a

reference to the total failure of the Hotspot and relocation system.

This is a Europe, in sum which for fear of giving too much ground to

the populist right, ends up assuming their positions, even if

mitigated by a less vulgar or openly racist tone.

At

Pozzallo there were two landings following one day after the other,

while only the night of August 30th

the English vessel “Fast Sentinel”, although originally directed

towards the Ragusan port, was redirected to Porto Empedocle with 300

migrants on board, because the situation at the Hotspot seemed

unsustainable. The condition of the dozens, if not hundreds, of

unaccompanied minors, both male and female, present in the Hotspot

for weeks is equally unsustainable. The lack of appropriate available

places is no justification for the violation of human rights and

arbitrary, illegitimate detention in a place which is entirely

inadequate, and without any appropriate separation between men and

women, adults and children.

We know

that often within the centre there aren’t even enough mattresses, and

the physical sleeping space and conditions of overcrowding have by

now become chronic with the new arrivals. Only a week ago we met some

young men who had run away from the Hotspot a week earlier, who were

aware that they needed to wait for available, appropriate places, but

not the fact that their presence in the centre had no legal basis,

above all for such a long period. “We have Italian lessons, clothes

and regular food in the centre. But waiting is too hard, it almost

makes you ill, even more so because we see other people are

transferred and we’re too many”, says A, from Gambia, who has been

acting as an impromptu translator, including for his friends from

Mali and Eritrea. “I know a lot of languages, I want to study and

here I’ve already learned some Italian words. My friends haven’t,

they haven’t even gone to school, which is why they can’t make

themselves understood.” A’s friends will still have to keep waiting

until the point when, one hopes, they will arrive in a place where

they can be more than just numbers and instead make themselves

understood and be known as human beings. But in the meantime the maps

of Italy and of Europe which these young men have received continue

to be sketched with a geography of voyages and dreams which remain

imaginary for whoever cannot move themselves freely, in which they

differ from their European peers.

The 473

migrants who arrived yesterday at Pozzallo have followed the same

process as the 692 who arrived less than 24 hours previously, among

whom there included 40 or so unaccompanied minors and around 20

pregnant women. The disembarking of the OOC Jaguar merchant vessel,

planned for 8am on Thursday, was delayed by 4 hours by the medical

checks undertaken by USMAF; it seems in fact that the merchant vessel

did not have any medical staff on board, and that it had not been

possible to undertake the routine checks immediately following the

rescues. There was a large deployment of police forces, along with

Frontex agents, members of EASO* and workers from the Red Cross, the

UNHCR*, IMO*, Save The Children, Terres Des Hommes, Emergency and

MEDU.

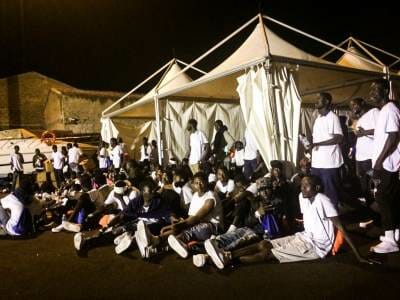

The

nationalities of the migrants present were varied and heterogeneous:

Gambia, Guinea and Mali, but also Bangladesh, Senegal, Egypt, Syria,

Somalia, Cameroon, Nigeria, Tunisia and Morocco, all having departed

from Libya like their companions from the day before. From the

Hotspot, the transferrals continue to Campania, Abruzzo, Molise and

the Central North, but last night a hundred people spent the night in

tents set up at the port by the department for Civil Protection.

Among them were women, children and Eritrean and Syrian families.

This is similar to Augusta, where around sixty minors were landed on

Wednesday and are still hosted in the tent-city at the port, along

with another 600 people. Yesterday, after the go ahead from the

doctors, the long descent under the beating midday sun began, the

refugees waiting in line for the photo, the scrupulous metal detector

checks, and the unending series of questions from the police and

Frontex agents, who are ever more active on the quayside. The landing

operations lead onto the removal of the witnesses and presumed boat

drivers/people smugglers, the alighting onto the buses and the

accompaniment to the area of the Hotspot, far from prying eyes.

Darkness and silence, all too frequently along with a lack of

protection for human rights, thus return to the migrants, who have

only just escaped from the jaws of death.

Lucia

Borghi

Borderline

Sicilia

Project “OpenEurope” – Oxfam Italia, Diaconia Valdese, Borderline Sicilia Onlus

*EASO:

European Asylum Support Office

*UNHCR: UN

Refugee agency

*IMO:

International Migration Organization

*MEDU:

Medici per I Diritti Umani – Doctors for Human Rights

Translation:

Richard Braude