Deaths at the Border. Control and Repression Replacing Reception

“Four survivors from a ship packed with 193 people”. “The numbers of missing are imprecise, but in the hundreds.” “Eight bodies but a massacre feared”. By now we do not speak about the dead, but those who did “not survive”, making calculations by exclusion. It is increasingly difficult to know how many people continue to lose their lives at sea. Understanding how many victims our borders have claimed is simply too shameful. Since the beginning of 2017, 240 people have already died crossing the Canal of Sicily, and we are only half way through January.

And yet the journeys of death, violence and disappearance unfold before our eyes every day, the stories of those struck down by a rationality of closure and inhumanity of countries like ours where wealth is gathered and consumed but rarely produced, and so our own economic interests have to be defended by force.

The invisibility of those who remain tormented by months of torture and under the threat of death in Libyan prisons, of those who disappear at sea and in the desert is equal to that of those who manage to arrive in Italy, where the discussion regarding migrants is reserved for the subject of implementing means of controlling and repressing them. In a society based on communication and writing like our own, public discourse, political slogans and the phrases of the day “create” the image of the refugee to suit specific ends, not in order to match up to reality. In the last few weeks the news about the next immigration deals has picked up an alarming pace in newspapers and TV, with announcements about getting a grip on rejections, the opening of new detention centres (CIE*) under military control, fast-track expulsions for those refused international protection, agreements with North African countries just as unlikely as they are crazy, and obviously the usual hypocritical fight against trafficking.

It would be useless to repeat how clearly our system of militarising the borders simply throws migrants to the traffickers, rather than saving them. Without any possibility of legal and safe passage, whoever is fleeing has to do so by paying an ever higher price.

The struggle against human trafficking remains merely a paper promise, as much as the protection of vulnerable persons. And so the hundreds of arrests of “suspected boat drivers” continue to mean nothing less than the criminalisation of people who we know have themselves been victims of forced conscription, and whose arrests have brought to light almost no connections to the real organisers of the sea voyages. At the same time, dozens of Nigerian women, bound to international circuits of trafficking and exploitation, are practically abandoned after they arrive in Italy. Only a small number of them are given assistance, and inserted into appropriate courses of protection, while the others find themselves left in emergency centres where criminal networks find them with no great difficulty. “Since I’ve been in Italy I’ve seen around ten young women from my country leave the centre after a few days here. I also wanted to go but I was ill and couldn’t. I was lucky that I was found by some people who I could trust and spoke my language, but how many people does that happen to?” ‘P’ tells us, a Nigerian woman hosted in an “emergency” centre in the province of Catania.

And so dozens of unaccompanied minors also turn “invisible”, increasingly crammed into centres of ‘first reception’ (CPA*), where around 50 people live on average, remaining there for an undetermined period of time. “In August lots of people and associations came to visit our centre”, ‘S’ tells us, who has spent 5 months living in the Extraordinary Reception Centre (CAS*) for minors at San Michele di Ganzaria. “They came about the problems some young Egyptian guys had. Then it went silent. We started school, but we’re always 7km away from anywhere else, completely isolated.” “From when I arrived in November, I’ve seen around twenty new people; two were with me in Libya. They stayed a week, and then one morning we couldn’t find them”, ‘C’ tells us on the other hand, who has been in one of the many other centres of ‘first reception’ spread throughout the small towns around Catania. “The staff here don’t remember our names, but only our countries. The Gambians and the Nigerians are known as being ‘difficult’. That’s what they think about us even before they meet us, that’s why I don’t trust anyone.” Arriving in a democratic state does not equate to having fundamental rights, the protection of which is far too often still something one finds in a few “fortunate” cases.

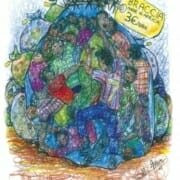

The reception system in Italy is about to be replaced by still more stricter means of control, selection and repression, destined to create nothing but suffering, rage and violence. Policies directed along these lines, asides being in contravention of international agreements and laws, are clearly incapable of guaranteeing basic human rights. Behind the numbers of deportations, expulsions and detentions there are people who have been judged only on the basis of the country they have come from, and not their individual stories. In the view of anyone who supports the repression of “irregulars”, there is an agreeable image of migrants as living threats rather then men, as nothing more than the perfect scapegoats to whom the people can turn to pour out all their unease and dissatisfaction. The “numbers” of the reception system hide the women, men, minors and families forced to live in centres which are inadequate both structurally and in terms of organisation, where frequently not even four walls are present to keep out the winter cold, but just a large tent.

While the images of migrants succumbing to the cold on the Balkan Route run before our eyes, joining others dying on the borders, many of the refugees we have listened to recently tell us about still having thin clothes and shoes while it snows outside. Others received electric heaters only a few weeks ago, after numerous requests and two months spent in the freezing cold; others still, together with some of the workers in the centres, have officially reported the total lack of heating, in one of the harshest winters in recent years. This is what’s been going on in the Extraordinary Reception Centres, and also in the initial reception centres (CPA*) for minors, managed by the cooperatives which have won the regional bids.

The situation is, without doubt, no better in the larger towns, where big tents have been set up to deal with the cold snap, housing the homeless, migrants and otherwise. These situations range from that of Ragusa – where there is practically no support aside from a somewhat symbolical remedy by the Red Cross, offering sanctuary in a tent for around ten days – to that of the 50 sleeping in Piazza del Pantheon in Syracusa, all the way up to that of Catania, where for a few days hundreds of people simply wandered the streets.

Many migrants are entirely aware that they have not been welcome but rather materially, legally, symbolically and consciously locked out from our society. Their general lack of voice leads to episodic explosions of anger, all too easily stigmatised by those who have no wider vision of our current context. Migrants’ own demands often arrive only via a warped discourse, through suspicious and reticent phrases, demands which, in the end, bear the heavy weight of the humiliation to which people have been subjected. Their bodies are stricken with trauma, frozen by the cold and by fear, but they continue to move, reaction, walk, searching for somewhere safe, for a job, for some connection to the place they are in. For that dignity which we all have in common, and for which they are sacrificing their entire existence.

In Catania some tent structures were set up first by the Red Cross, which gave out hot meals and the possibility to sleep under covers to around 40 people each week, until the baton was passed to the Misericordie, who are providing the same service near to the station, but for a much shorter period. “Lots of migrants come through here, not just Catanians” one of their volunteers told us, “lots come from Mineo, and want to leave the city for good; lots are clearly minors, and they don’t speak a word we can understand. It will be a disaster, but at the weekend they’re saying that the weather will improve, so we’ll have to pack up.” And indeed, on Saturday morning the tents had disappeared from the square. At the last meeting of the city council, there was the expressed intention to set up a new dormitory for the homeless, but it isn’t known when or where this will happen. Meanwhile, a weather warning has been announced across the city.

Lucia Borghi

Borderline Sicilia

Project “OpenEurope” – Oxfam Italia, Diaconia Valdese, Borderline Sicilia Onlus

*CAS = Centro di Accoglienza Straordinario (Extraordinary Reception Centre)

*CPA = Centro di Prima Accoglienza (Initial Reception Centre)

Translation by Richard Braude