Madi, Houssein, and the Other Nameless Ones

Article first published on June 10, 2021

Currently, we can no longer cope with the requests for help that reach us from migrating people who have lost everything. More and more often they are condemned to slavery and invisibility by the political-institutional system, which destroys them physically and psychologically.

These types of abuses are relentlessly repeated and often result in death. We try to draw attention to this as much as possible, but lately this is even more difficult due to the obstacles that Covid-19 has put in our way. However, the closures wanted by the institutions and instances of abuse in the reception centers and police headquarters of Sicily keep happening.

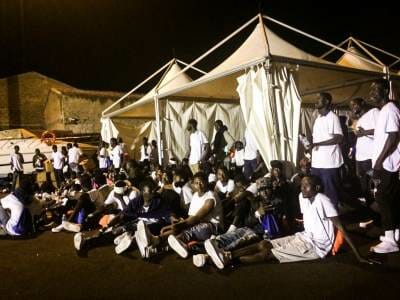

The word abuse is, in our opinion, the most appropriate with regard to the gathering of people in front of the police headquarters. These are images that are in strong contrast with the situation in which we currently live and are unacceptable in any case, regardless of the current pandemic. Inside the Palermo police headquarters there are huge spaces, but until today no police chief has thought about the fact that it is indecent to treat people like animals, huddled together for hours, sunshine or rain. They are waiting for an answer, which they often do not even get. The same dynamics of abuse are repeated every day for those impoverished and invisible in any context in which they live, humiliated and left alone. Covid-19 has exacerbated an already unacceptable situation and has caused even more “inhumanity.”

Madi is just one of the many victims of this system that tends to erase people. He arrived in Italy in 2016 and was immediately detained in the large reception center of Mineo. Since this center has been open, it has led to the enrichment of various people close to political milieus and organized crime, many of whom still today, despite various trials, continue to be part of cooperatives working in the reception sector. In 2019, after the denial of international protection and the appeal filed by a lawyer from Rome (the same situation affects many other asylum seekers placed in the center in Mineo), he was transferred to the extraordinary reception center Bellolampo in Palermo after the closure of the center in Mineo.

His transfer took place without any verification of his physical or psychological condition, or his social situation – as if Madi had never existed in Mineo. From the beginning it was clear that he had difficulties, especially psychological ones, with many ups and downs. The staff of the center tried to understand and support him, but extraordinary reception centers are not adequate facilities for reception, especially not for people who have problems related to some form of vulnerability. Toward the end of 2019, Madi decided to leave the facility on his own, despite the fact that the staff present tried to dissuade him from the idea. The last contact with a staff member at the center occurred in January 2020, when he arrived in Germany, probably with the help of someone who took advantage of his problems.

Since then, his life has been a black hole. No one, not even relatives who live in Palermo, know what Madi did, where he lived, until the morning of May 3. On that day, a staff member of the extraordinary reception center, purely by chance, had to identify the body of a young man who had hung himself in the field in Bellolampo. “From a distance I see a body hanging from a tree, I get closer, I recognize the hands, but I’m not sure if it’s him. I get closer, I see the right side of his face: it is Madi. The boy’s body was 10 km from the reception center that housed him until October 2019. I stayed there with the police, the inspector, the staff of the ambulance… I do not remember how many hours I stayed there, under the rain with the young man’s body hanging from the tree. If I hadn’t recognized him that morning, who knows if we would have ever known about his death.”

Madi died without receiving a response from the Italian justice system regarding his appeal, without proper legal and psychological help. Madi died alone, in a solitude wanted and organized by the political system.

This system claims victims every day; they do not make any noise anymore. We are so used to it that when four Black people die in a traffic accident, we do not even ask questions anymore: were they someone’s sons, husbands, brothers? Will their family members ever know?

The system erases them. Only a few news headlines pop up to avoid thinking and reflecting on the fact that these people are needed for our economy, and their deaths are just insignificant collateral damage. However, we give a name to these dead people because we know that for the dead in the sea, at work, the dead due to misery and poverty, there are people who are responsible for, people who are in the highest positions of the institutions, unions, up to our ranks, every time we turn away.

The sea also washes up the bodies of those who arrived in Italy a long time ago, such as a Nigerian without a name, found in recent days on the banks of the Fontane Bianche in Siracusa.

An invisible young man who, in order to survive, was begging and living in a small tent next to the beach where he was found. A nameless invisible man, another one who must quickly disappear from the news even in this case, because the summer season is about to begin and Fontane Bianche is a tourist location.

Other victims of this criminal system are those deaths that continue to happen inside the detention and repatriation centers at the borders. Not to speak of the war against the NGO ships that are detained under flimsy pretexts that clearly show the extent to which politics wants to suppress sea rescue.

A few days ago, a subtle reference was made on the part of the government with regard to the system of quarantine ships, which is to be abolished, but so far nothing has been done. Despite official statements regarding the fact that unaccompanied minors are not allowed on the ships, they have been seen there. This possibly happens because no information about them is registered at the Lampedusa hotspot, so it is only on the ships that it becomes clear how old the young people are. But once they are on the ship, they cannot leave it until they have been quarantined with a negative test. In the last month, various cooperatives that take in minors have gone to Sicilian ports and picked up the young people in order to take them to their facilities. This was also the case with the landing of the ship Azzurra in Catania two weeks ago.

The fact that quarantine ships are an illegal, discriminatory and human rights violating practice we have already seen with the case of Houssein, a young man who boarded the quarantine ship Allegra last April 6. He was able to take a negative rapid test right away, however the result of his test was positive just before he left the ship, and so he had to start the quarantine all over again. Houssein has severe mental health issues and no one on the ship was aware of it, not even during the initial screening.

The Red Cross medical staff only noticed this after one of Houssein’s friends spoke to a mediator. The doctors discovered then that Hussein suffers from severe nail dystrophy on eight out of ten nails, as a result of the torture he suffered in Libya. He bears other signs of it on his body, and above all he suffers from a psychological vulnerability, also due to the violence he suffered. In addition, he has lost contact with his girlfriend, who was raped several times in front of him by Libyan killers. Houssein was declared in need of protection under a red code representing shock and trauma two weeks after arriving on board.

On April 24, he was tested again before his scheduled departure from the ship on April 26, but he was still positive and isolated for a third quarantine, this time alone, as his companions tested negative. Houssein became angry, knowing he would have to remain alone on the ship, and openly stated that he would end his life because everyone had abandoned him. Only when pressure was exerted from various parties he was admitted to the psychiatric department of the hospital in Catania.

In these few lines, avoidable deaths pile up, deaths that we have been forced to talk about for too many years, to denounce the institutional and systematic violence that lies behind them. We must continue to do so and not let the defense of rights slide, so that no one ever again has to die alone at the bottom of the sea or without a name.

And once again, we apologize to Madi, Houssein, and to many other invisible victims of an unjust and criminal system.

Alberto Biondo

Borderline Sicilia

Translation by Annika Schadewaldt