Boys on the Outside. Activists on the Inside.

The day before yesterday the head of stat gave the green light for the most unjust and inhumane law since the post-war period till today. We know from experience that this is a law that will hurt everyone (other than ‘first the Italians’) because it attacks rights, and that cannot help anyone (other than traffickers and Mafia), but only feed hatred and social conflict.

The first effects have been seen in the closure of many emergency hostels (CAS)* run by the prefectures, as well as spot checks to verify the possible presence of people with a permit to stay for humanitarian reasons, to be shown the door. In Palermo three CAS were closed last week and others have had their purpose of use altered. The centre Azad/Elom which was previously a structure for minors has for some time become a CAS and today “contains” more than 140 asylum seekers. The same situation has been noted in other Sicilian cities, and on the mainland. As was entirely predictable, the new law – aside from destroying the already unstable reception system – is creating countless difficulties for councils and local authorities: tendering processes suspended, contracts ended unilaterally and work places lost from one day to the next. In a context such as this, there are obviously illegal practices, such as those of some council registration officers that have decided to block all enrollments for foreign citizens, such as in Palermo, Alcamo and Marsala, to cite but a few.

The first effects have been seen in the closure of many emergency hostels (CAS)* run by the prefectures, as well as spot checks to verify the possible presence of people with a permit to stay for humanitarian reasons, to be shown the door. In Palermo three CAS were closed last week and others have had their purpose of use altered. The centre Azad/Elom which was previously a structure for minors has for some time become a CAS and today “contains” more than 140 asylum seekers. The same situation has been noted in other Sicilian cities, and on the mainland. As was entirely predictable, the new law – aside from destroying the already unstable reception system – is creating countless difficulties for councils and local authorities: tendering processes suspended, contracts ended unilaterally and work places lost from one day to the next. In a context such as this, there are obviously illegal practices, such as those of some council registration officers that have decided to block all enrollments for foreign citizens, such as in Palermo, Alcamo and Marsala, to cite but a few.

Over the last few days we have had the honour of meeting Adam, Ibra, Mohammed, Rajib, Demba, Fathia, Adrea, Tiziana, Marco, Irene and Fulvio (not their real names), young people brought together from different backgrounds who are all victims of the same unconstitutional law.

Adam now sleeps in Palermo at one of those Five Star Hotels about which politicians speak so often to make propaganda: a mattress in a piazza near to the central station. He’s 19-years-old and each morning he manages, with great dignity, to go to school, while in the afternoon he begs in one of the many shopping centres in the city (“it’s the only one where they haven’t told me to go away”). Lunch and dinner are optional, while washing himself is only possible thanks to the associations present in the city. Rajib also shuttles between the various charitable centres in Palermo, and he manages to get a few coins together by looking after a flower stall. Ibra and Mohamed on the other hand have made a more ‘radical’ choice: they’ve gone to fill up the lines of the invisibles and are currently at Campobello for the olive harvest, exploited, but they arrived late in the season and the harvest is over, so they don’t have money in their pockets even to eat. They are simply waiting for the caravan of slaves to move onto another place to join in. Of the two, Ibra has a clearer idea. Perhaps because Mohamed was followed from the start by the health authority in Palermo due to psychological problems deriving from the Libyan hell, which don’t leave him in peace even for one night. When we met him he wasn’t doing well, but the law doesn’t want Mohamed to be helped, accompanied, it doesn’t want him to forget the inferno – no, the law wants to keep him there.

Adam now sleeps in Palermo at one of those Five Star Hotels about which politicians speak so often to make propaganda: a mattress in a piazza near to the central station. He’s 19-years-old and each morning he manages, with great dignity, to go to school, while in the afternoon he begs in one of the many shopping centres in the city (“it’s the only one where they haven’t told me to go away”). Lunch and dinner are optional, while washing himself is only possible thanks to the associations present in the city. Rajib also shuttles between the various charitable centres in Palermo, and he manages to get a few coins together by looking after a flower stall. Ibra and Mohamed on the other hand have made a more ‘radical’ choice: they’ve gone to fill up the lines of the invisibles and are currently at Campobello for the olive harvest, exploited, but they arrived late in the season and the harvest is over, so they don’t have money in their pockets even to eat. They are simply waiting for the caravan of slaves to move onto another place to join in. Of the two, Ibra has a clearer idea. Perhaps because Mohamed was followed from the start by the health authority in Palermo due to psychological problems deriving from the Libyan hell, which don’t leave him in peace even for one night. When we met him he wasn’t doing well, but the law doesn’t want Mohamed to be helped, accompanied, it doesn’t want him to forget the inferno – no, the law wants to keep him there.

Demba called us because he wanted a final embrace, after we had tried to support him with legal assistance, given that in his hostel he hadn’t received any help whatsoever. Demba had to pack his bags and took a bus straight to Rome, telling us that “life hasn’t given me anything, instead it’s just taken things from me, starting with my parents and my little brother. I wanted a new life, I wanted a little happiness, but Italy wants us blacks to be unhappy, it just wants our sweat, our anger. But you will never have this from me, I’m not going to let a few racists win out. I can give you what I am, a young man who wants to live life because I’m tired of death, so I thank you for everything you people have given me.” I didn’t have the courage to look Demba in the eyes until he had got on the coach.

Fathi is the “luckiest”, a young man with bright eyes who caught our attention immediately because of his upbeat nature, his smile, which clearly influenced the choice of his former guardian, Tiziana, who had the opportunity to meet him when he was still a minor. They have walked together over the last year, facing the difficulties of the reception system. Tiziana did so with a necessary dose of humanity. And today, in the moment in which Fathi has lost his place in a CAS* in Partinico, he has come to live with Tiziana, awaiting better times. But Fathi is one of the few people who have a guardian who has taken on the full weight of her voluntary activity, because instead what we are gathering is a long list of worst practices, of minors abandoned to themselves, above all in the provinces of Agrigento, Trapani and Enna.

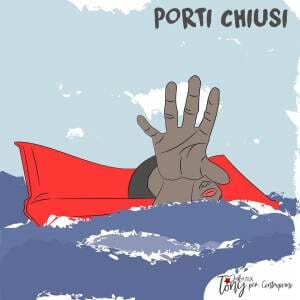

Irene, Andrea and Fulvio, on the other hand, are some of the young people who have lost their jobs and are still waiting for more than a year’s wages. Andrea is a husband and father; Irene is a single mother; Fulvio has just fixed the date for his own wedding. All of them chose to enter the field and try and provide a decent situation for the residents in their centre, but today – along with many others – they find themselves with the short straw. They are desperate – surely in a way different from the migrants – but they are united in the inhumanity waged against them. An inhumanity that has pushed migrants out of the hostels and has pushed unemployed Italians back into their houses – or for some activists, into prison. This government wants to hit anyone who rebels against their inhumanity with every means available, people who have struggled in silence to help those who are worse off, to save lives at sea or try and give a future to those who do not have one. The strategy is to smear, pursue and crush – including psychologically – until no one is left to struggle for what is right. But fortunately there are stories of the young people we have met, and their network of support. We are sure that there is an opposition to the Fascist turn in our country, witnessed by the solidarity of the NGOs under attack, but the taking a stand by the psychologists and social workers, by the appeals by so many associations and watchdogs, and – despite everything – the NGOs’ return to the sea.

Finally, we should recall that this law is the desire of almost all of parliament, because 336 MPs voted “yes” and the President of the Republic signed it off, despite its clearly unconstitutional characteristics. This means that it is up to us to make the move, not only by opening the doors – as we have done many times in the past – but also by trying to tell things as they really are, by bringing to light stories like those of Demba and the others, because the only way to struggle against death is LIFE.

Alberto Biondo Borderline Sicilia

*emergency hostels = Centri di accoglienza staordinaria (CAS)

Project “OpenEurope” – Oxfam Italia, Diaconia Valdese, Borderline Sicilia Onlus

Translation by Richard Braude